Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus)

Photo of an adult Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake by Giselle Ashley

Description: The heaviest pit viper in North America, the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake can weigh up to 15 lbs and reach lengths of 4 to 5 ft, on increasingly rare occasions 6 ft long. Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnakes have a dark diagonal line running through their eyes with tan highlights, their backs have a pattern resembling jagged edged diamonds with light tan highlights. Also common among pit vipers are heat-seeking pits, ridged supraocular (above the eye) scales, and solenoglyphic (singularly mobile) fangs attached to their venom glands.

A darker adult Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake with broken rattles (Photo by Giselle Ashley)

Diet: these beautiful forces of nature primarily eat rabbits and squirrels as adults and rodents when young. Their modified saliva (venom) has evolved to better break down and digest mammals as a result.

Photo by Giselle Ashley

In the wild it’s been known that Rattlesnakes can live 20+ years, however, they’re often killed as soon as seen. With habitat destruction on the upswing, spotting adults of breeding age (5+ years) is rapidly decreasing as their numbers are drastically diminishing. A petition to protect them federally under the endangered species act via USFWS was initiated in 2011, so far to no avail.

Photo credit to: the awesome Chase Pirtle. A true warrior on the front lines of education and conservation of the natural world.

Breeding/birthing seasons: In Florida, Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnakes mate in the late summer and fall. Females often give birth to around 8-29 live young between August and September. Giving birth to live young happens with all Pit Vipers (5 of our 6 venomous natives are pit vipers.)

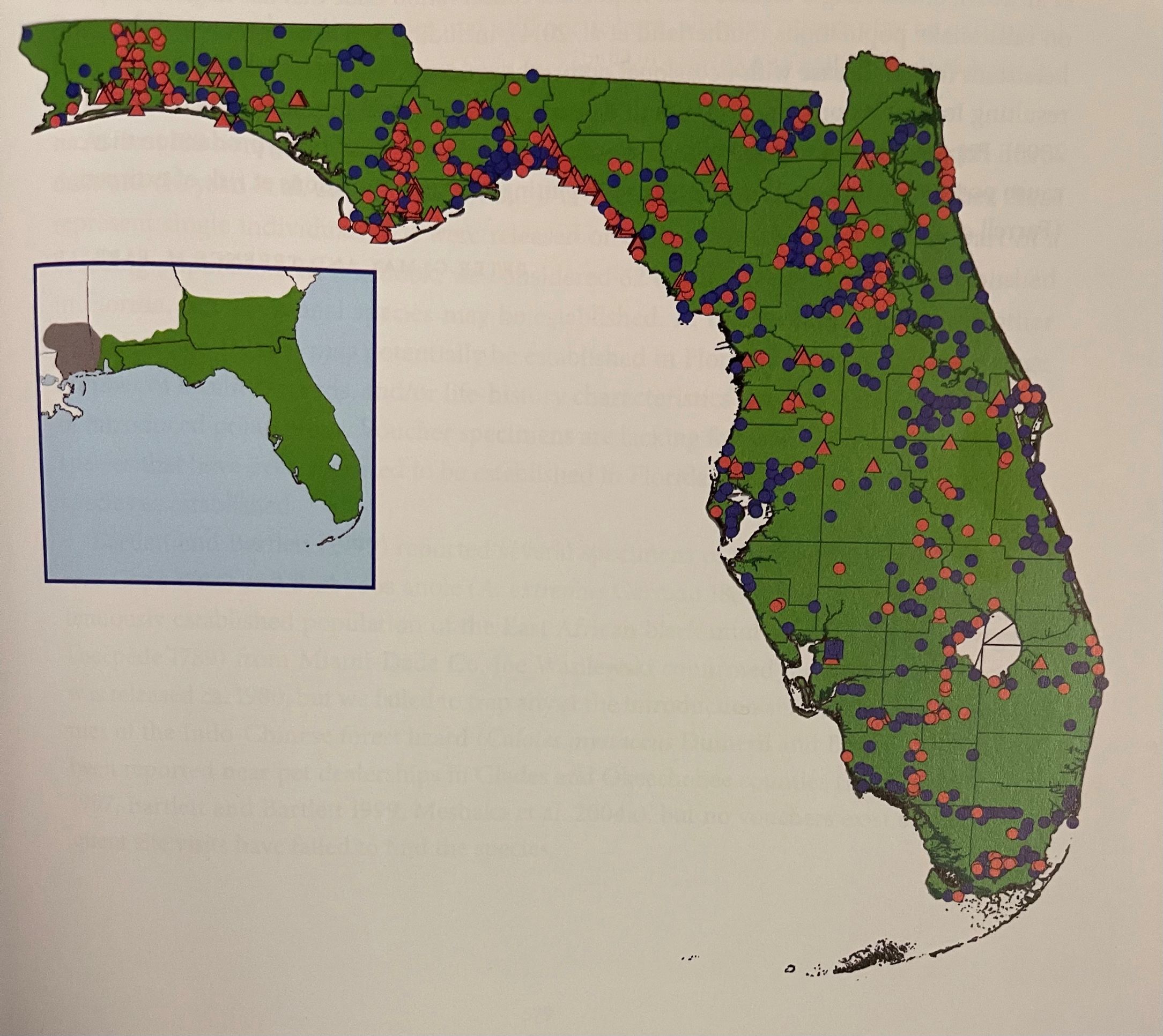

Range map from the amazing book: Reptiles and Amphibians of Florida

Habitat: Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnakes range the entirety of FL. They can be found in dry sandy areas such as: scrublands, barrier islands, upland pine habitats, palmetto or wiregrass flatlands, and coastal forests.

Canebrake (aka Timber) Rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus)

Photo of an adult Canebrake Rattlesnake by Giselle Ashley

These forest guardians were nearly chosen as the national symbol for America when Ben Franklin wrote: “I recollected that her eye excelled in brightness, that of any other animal, and that she has no eye-lids. She may therefore be esteemed an emblem of vigilance. She never begins an attack, nor, when once engaged, ever surrenders: She is therefore an emblem of magnanimity and true courage. ”

Photo of a juvenile Canebrake Rattlesnake by the amazing naturalist and herp enthusiast, a beautiful mind when it comes to the wilds of Florida: Prestin Tomborello.

Description: Canebrake Rattlesnakes can have some of the most color/vibrancy variability as they have the largest range of any snakes in North America. When visible, they can have chevron patterns down their sides, gold cheeks, brown or orange stripes running their spines, pastel blue beside their spines, pink underbellies, black tails, and tan chins. Some can be completely obsidian black (found typically much farther North than Florida where the common name “Timber Rattlesnake” is more often applied.)

Photo of an adult Canebrake Rattlesnake with visible chevron body patterns.

Diet: squirrels, mice, shrews, chipmunks, sometimes amphibians, other snakes, and on the rare occasion, carrion can be sustenance.

Breeding/birthing seasons: In Florida, females typically give birth to 6-10 live young between August and October. Females remain with their young for about one week until their first shed, after which they all disperse.Photo of an adult Canebrake Rattlesnake with visible chevron body patterns.

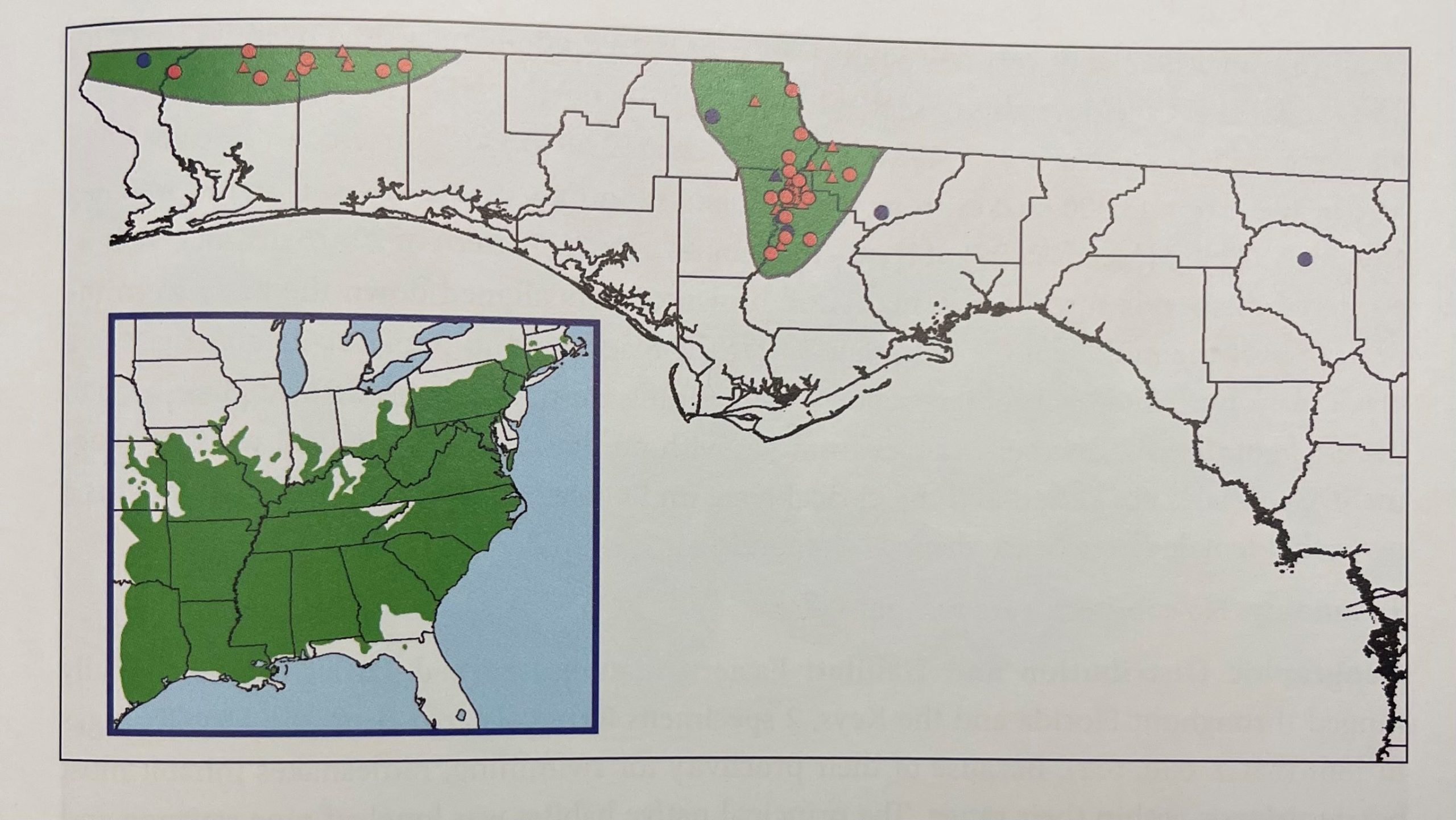

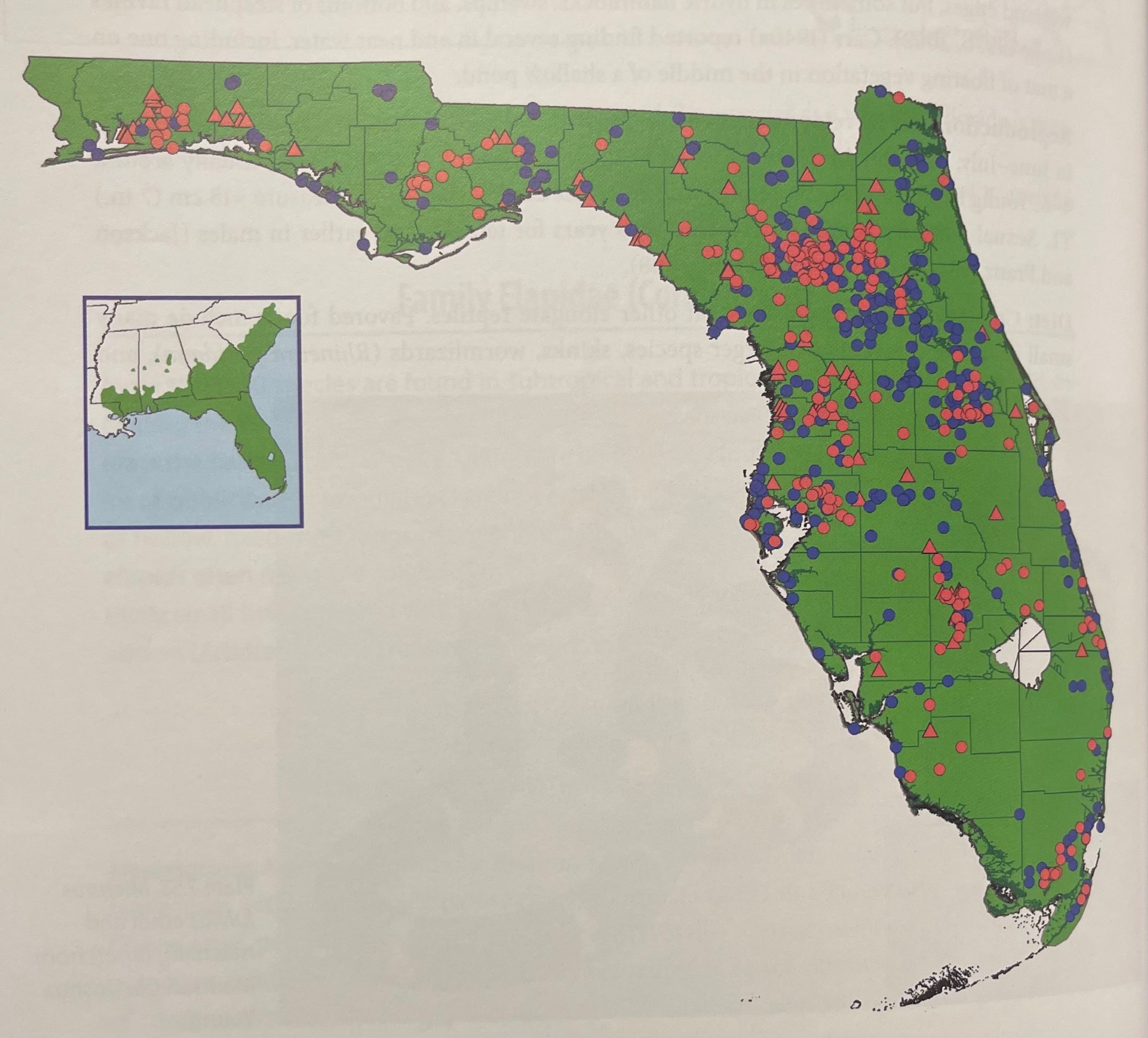

Range map from the amazing book: Reptiles and Amphibians of Florida

Habitat: Canebrake Rattlesnakes reside in lowland areas such as edges of marshes and swamps, cane thickets, wooded hillsides, heavy timber, and dead tree hollows. They inhabit a very small portion of Northern FL.

Cottonmouth (the Northern Cottonmouth, Agkistrodon piscivorous, and the Florida Cottonmouth, Agkistrodon conanti)

Photo of an adult Cottonmouth by Giselle Ashley

Description: Cottonmouths have a marbled chin, a dark band going across or through the eye, often with white highlights around it, a ridged brow above their eye (making it impossible to see their eyes if looking from above their head) heat seeking pits between their nostrils and eyes, vertical pupils (think like cat eyes) and jagged/pixelated lines that get wider toward the center of their body and closer together toward the spine or belly. Cottonmouths also often have polka dots or bullseyes in between those lines (one or multiple dots.)

Photo of a darker and relatively small adult Cottonmouth with visible jagged parentheses and polka dots in between them, a marbled chin, mask, and ridged supraocular scale are all visible. Taken by Giselle Ashley

Photo of a large and vibrantly patterned adult Cottonmouth with visible jagged parentheses and polka dots as well as a visible diagonally positioned mask.

Diet: a congeneric of Cottonmouth found N of FL has the scientific name: “piscivorus” which means “fish eater.” Aquatic and amphibious animals are a preferred prey but Cottonmouths can also be found eating carrion. They are relatively indiscriminate when it comes to obtaining nutrients and eating dead animals off the road can often mean expending less energy than pursuing prey.

Breeding/birthing seasons: from April to May, males will war with each other trying to overpower one another with their bodies (not resorting to using their mouths) to compete for a nearby female. The one who tires out, loses out on mating rights. Typical gestation is around 5 months.

Defensive reactions: Cottonmouths have an undeserved reputation of being aggressive or chasing. “Aggressive” entailing a will to harm, and “chasing” insinuating that they want to pursue a predator bigger than them. No records of this have come to light because this is a case of mistaken intent, the mainly instinctually geared creature moves toward safety while putting on defensive displays, if in the direction of a potential threat. Most often, Cottonmouths flee before anything else.

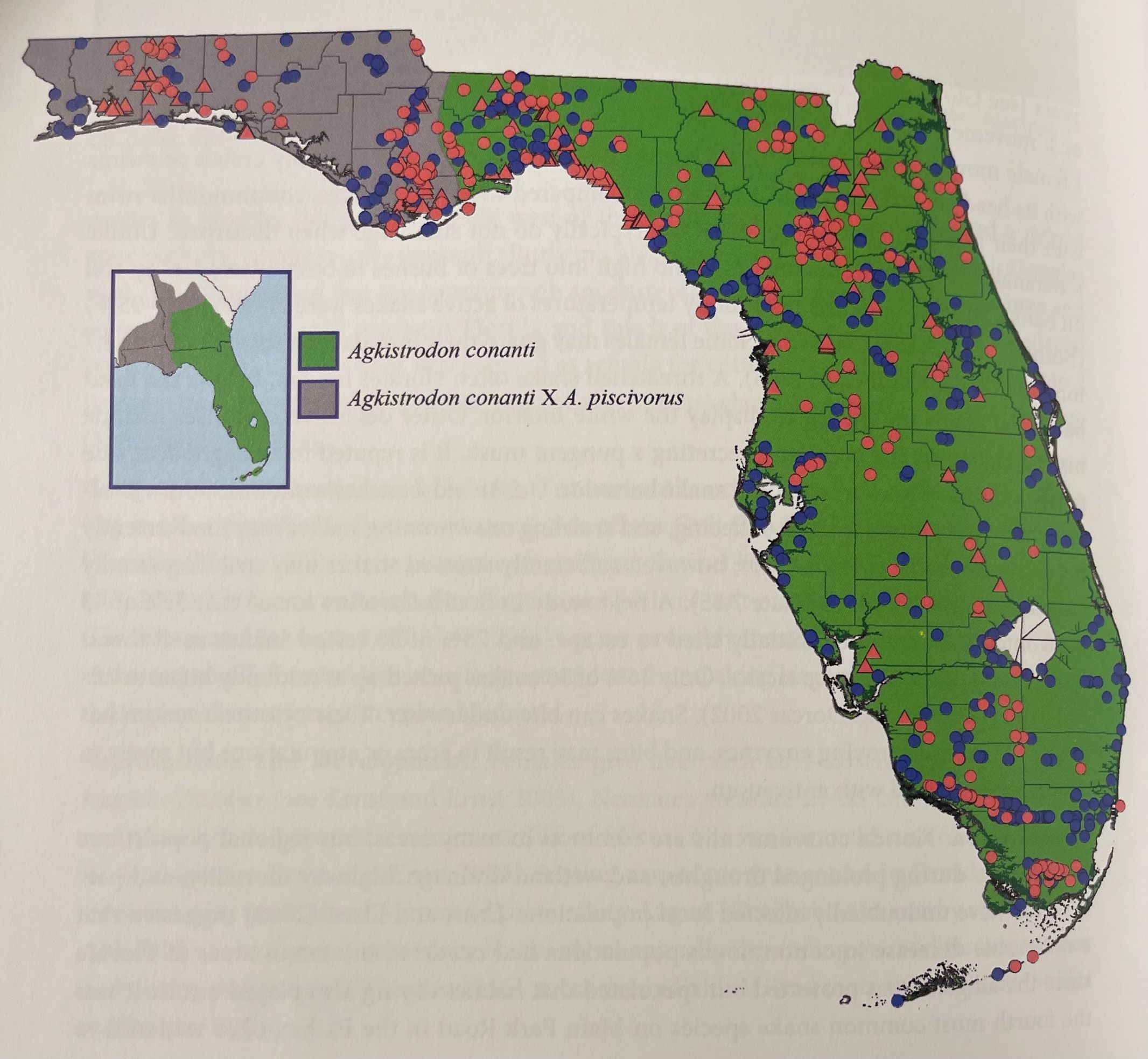

Range map from the amazing book: Reptiles and Amphibians of Florida

Habitat/Range: They can be found in every county in Florida in nearly all freshwater habitats but are most common in cypress swamps, river floodplains, and heavily-vegetated wetlands. Cottonmouths will venture overland and are sometimes found far from permanent water.

Eastern Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix)

Photo of a juvenile Copperhead by Giselle Ashley

Description: an often creamy, golden, and sometimes pastel pink colored member of the Agkistrodon genus, Copperheads are very closely related to Cottonmouths. Traditionally distinguished by their smooth Hershey’s kiss shaped patterns, some have polka dots between those patterns, golden/copper colored tops of their heads and more light tan colors from the middle of their eyes down. All typical pit viper traits are evident as well with ridged supraocular scales, vertical pupils (although not a great primary identifiable trait since pupils can dilate, appearing round in lowlight) and heat seeking pits that help them find prey that is warmer or cooler than their surroundings. Copperheads grow between 2 and 3 ft long, a bit less formidable than their Cottonmouth cousins.

Photo of an adult Eastern Copperhead with visible hershey’s kiss patterns as well as the common polka dots similar to it’s kissing cousin the Cottonmouth. Taken by Giselle Ashley.

Diet: notorious for feasting on Cicadas when they emerge, other insects, rats, other snakes, birds, and amphibians are also part of their diet. Copperheads are ambush predators and will often lie in wait, using their very effective camouflage for protection and predation.

A juvenile Copperhead with a chartreuse tail, hershey’s kiss patterns, and visible pit viper facial traits. Taken by Giselle Ashley.

Breeding/birthing seasons: breeding age is between 2 and 3 years old and mating occurs late February-May and September through October. Females can retain sperm from Fall matings for when they begin to ovulate in the Spring.

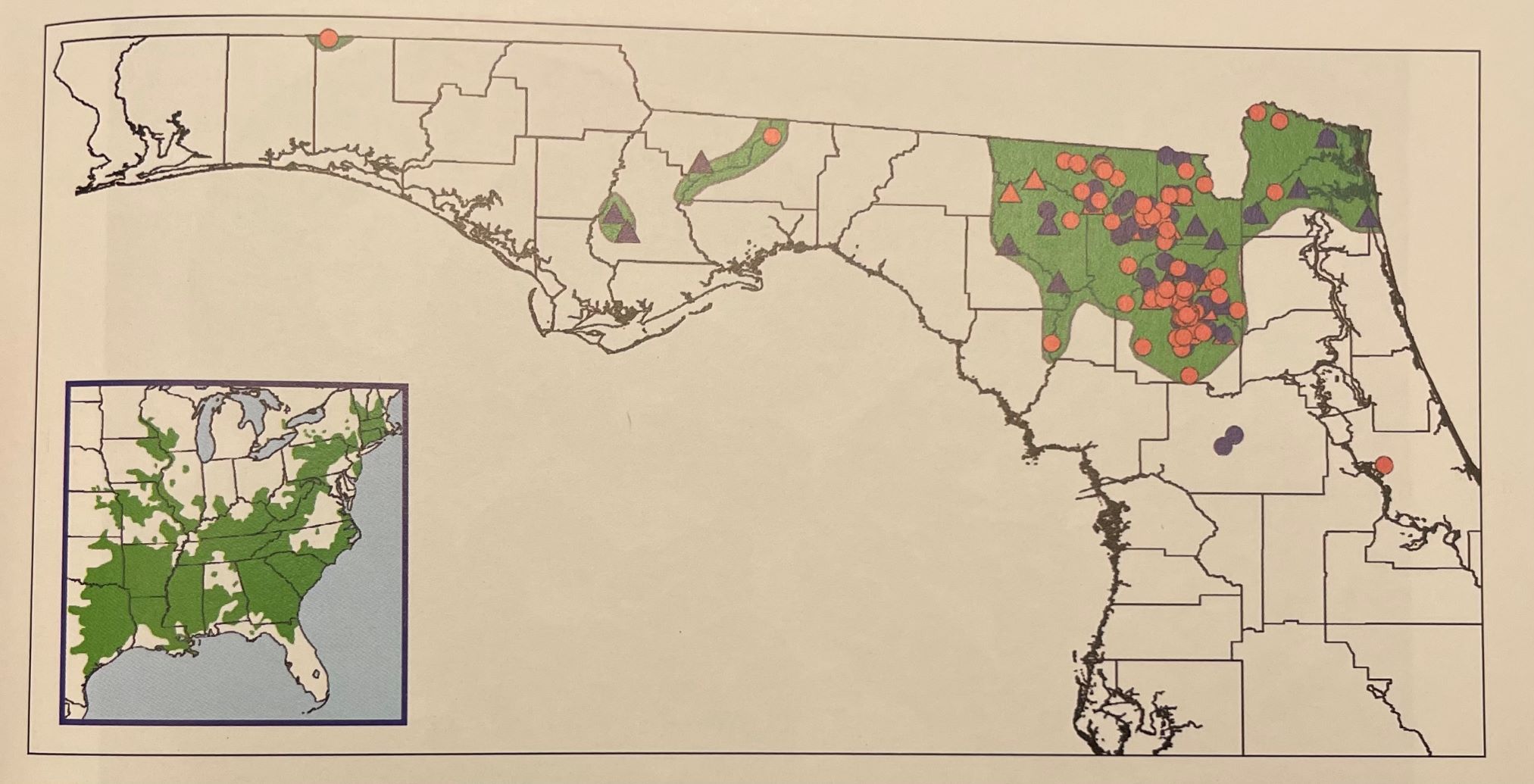

Eastern Copperhead range map from the amazing book: Reptiles and Amphibians of Florida

Habitat/range: only inhabiting a minute portion of N Florida in the Panhandle, these insect eaters range into hilly deciduous forests, rocky hillsides, flood plains, wetlands, edges of swamps in the South, and rotting woodpiles (a typical hiding/protection spot for snakes.)

Dusky Pygmy Rattlesnake (Sistrurus miliarius barbouri)

Photos of two typical colorations of our native Dusky Pygmy Rattlesnake by the wonderful Prestin Tomborello. Thank you so much for letting me use your photos for educational purposes. Your photography is absolutely beautiful!

Description: with a short, girthy body, Pygmy Rattlesnakes can be anywhere from 15-21 inches long when fully grown. They have rows of oblong ovals along their spine and faded blotch-like circles checkered between and underneath the oblong ovals. They can also have a reddish hue running down their spine as a stripe between the ovals but it’s just as likely to see a Dusky Pygmy without that red color as snakes in general tend to vary in vibrancy, pattern, and color due to genetics and environment. Pygmys tend to have a small rattle that sounds like an insect buzzing if heard at all and they’re less likely to be seen because of their size, accounting for a large percentage of envenomations but a lethal bite has never been recorded.

Photo of an adult Dusky Pygmy Rattlesnake with visible oblong oval body patterns by Giselle Ashley.

Diet: centipedes, frogs, lizards, snakes, and small mammals. They may actively pursue their prey, following scent trails, but typically resort to ambush-style predation like many pit vipers (expending less energy when possible and beneficial) and when young will also use their chartreuse tail as a caudal lure for bugs and lizards.

A neonate Dusky Pygmy Rattlesnake next to a quarter for size comparison. Photo credit: Giselle Ashley

Breeding/birthing seasons: A female gives birth to live young in late summer or early fall. Neonate Dusky Pygmys can be 3-7 inches at birth. Eventually young Pygmy Rattlesnakes grow out of the need for their greenish yellow tail and begin accumulating buttons for their rattles.

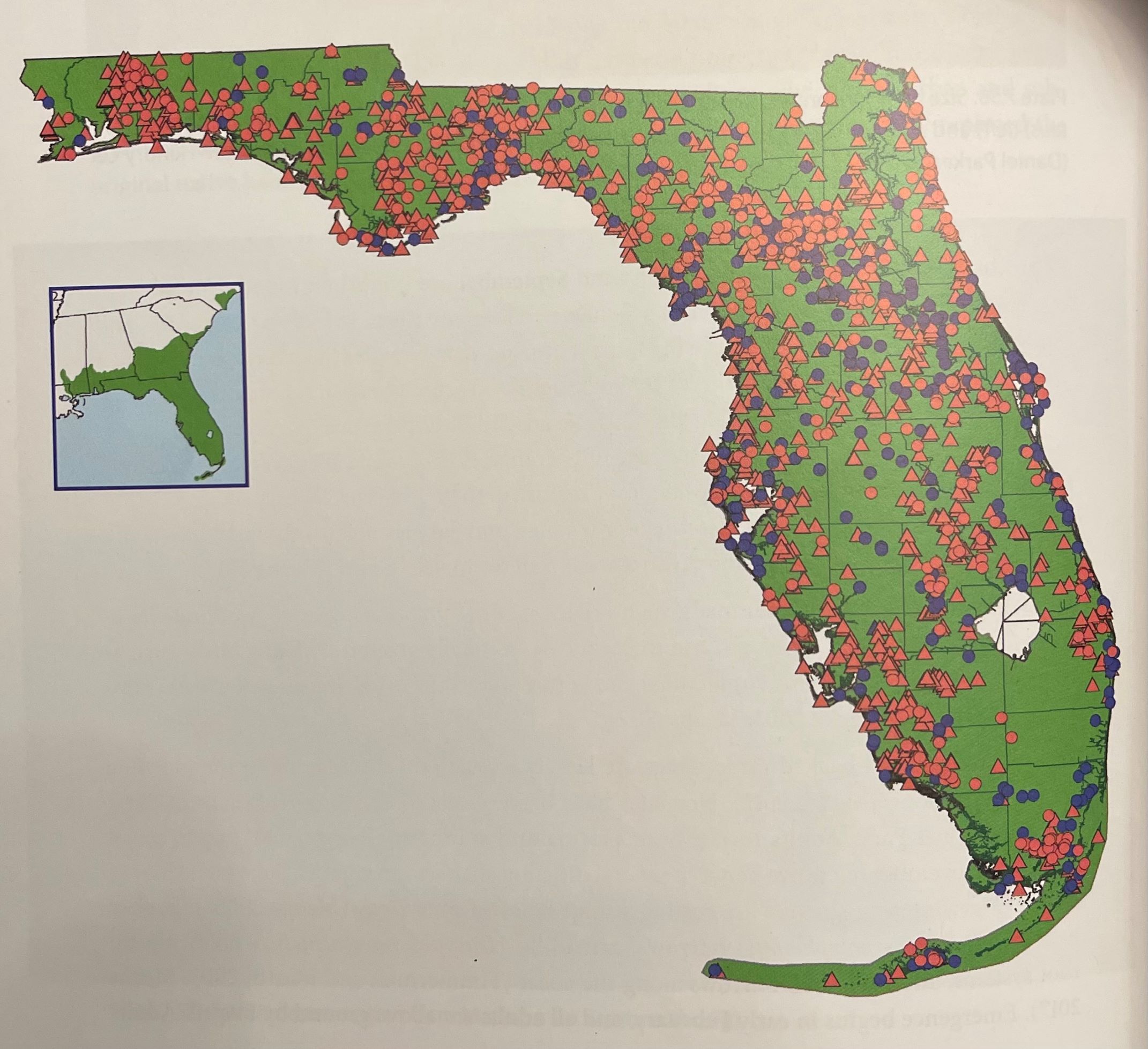

Range map from the amazing book: Reptiles and Amphibians of Florida

Habitat/range: they range practically all of Florida with the exception of the FL keys and have even been found on barrier islands. S. m. barbouri inhabits upland forests, sandhills, near to creeks, ponds, marshes, and swamps. Preferring shelter/ambush spots near logs or in low-lying plants.

Eastern (aka Harlequin) Coralsnake (Micrurus fulvius)

Prestin Tomborello’s gorgeous photo of a venomous coralsnake’s head.

Florida’s only native Elapid (related to cobras, mambas, and sea kraits) is a notoriously docile, elusive, and nomadic creature with front-fixed fangs and primarily neurotoxic venom (like it’s cousins.) Typically a fossorial species, coralsnakes tend to live and hunt lizards, smaller snakes, and bugs primarily underground or leaf-litter.

The amazing Tiffany Bright, SE Regional Director for The Rattlesnake Conservancy, certified Wilderness EMT, Master Naturalist, and Venomous Snake-handling Instructor took this picture of our only native Elapid.

Description: A slender bodied snake reaching between 20 and 30 inches, coralsnakes typically have blunt/rounded black snouts, a yellow/orange band next to that followed by another black band, and a pattern past that of: thin yellow, thick red, thin yellow, thick black.

Photo of a gravid (pregnant) Eastern coralsnake by Jack Facente, an incredible wealth of experience and knowledge when it comes to our only native Elapid.

Though their venom glands are small, their primarily neurotoxic venom is geared toward shutting down or overloading neurological communication from brain to vital organs; a little can go a long way.

This awesome photo of hatchling coralsnakes was shared by the wonderful Jack Facente, thank you so much for all of your help and input herein!!

Reproduction/egg laying seasons: according to the observation of 70+ coralsnakes by Jack Facente, coralsnakes can mate in the Spring and early Fall. 3+ year old females in Northern Florida often lay 2-18 eggs in decaying wood or loose soil between June and July and those eggs hatch between September and August.

Once reaching Earthside with the help of its eggtooth (used to tear its egg open) the 7.5 inch neonates brave the world underneath soil and leaves with full control over their venom output.

Range map from the amazing book: Reptiles and Amphibians of Florida.

Habitat and range: Eastern coralsnakes range the entirety of Florida and up the E coast as well as much of the NE gulf panhandles. They are fossorial and spend most of their time under ground or leaf litter. Mesic and xeric flatwoods in pine and scrub oak sandhill habitats but also sometimes hardwood areas and pine flatwoods that undergo seasonal flooding are also common places to find them.

Photo of me with my favorite venomous native: the Canebrake Rattlesnake.

Snakes are an integral part of our ecosystems and harmless if left alone. Venomous snakes also play a huge role in modern medicine, making way for breakthroughs in the prevention of blood clots and heart attacks (medicine derived from Dusky Pygmy Rattlesnake venom) and the study of Copperhead venom for it’s potential uses in treating Breast Cancer (so far slowing the growth and preventing the spread of tumors therein.) Venomous snakes have likely already saved the life of someone you know and love.

They’re not out to get anyone and not any worse a creature for evolving venom so they can eat more efficiently. They’re just doing what they were put here to do. But that’s becoming harder to do peacefully for them when their homes are destroyed, often forcing potentially confrontational encounters.

Avoiding a bite from any snake is as easy as gaining safe habits. Watching where we step or reach and if we can’t see into those places, using something long in our stead (a long stick or handle end of a broom) can help avoid surprising or scaring a snake and it’s as simple as our habit to look both ways when we cross a street.

I hope learning Florida’s 6 venomous natives (out of 44 total endemic snakes) helps in understanding them a bit more, helps you see what a snake is, or often is not, and helps in gaining some sense of understanding and feeling of purpose in our coexistence with them.

Without them, our wild Florida would be even more fragmented and weak than it already is. Understanding and encouraging their presence as mid-level predators also increases the chances that for our children (and theirs) we may continue to have a wild Florida.

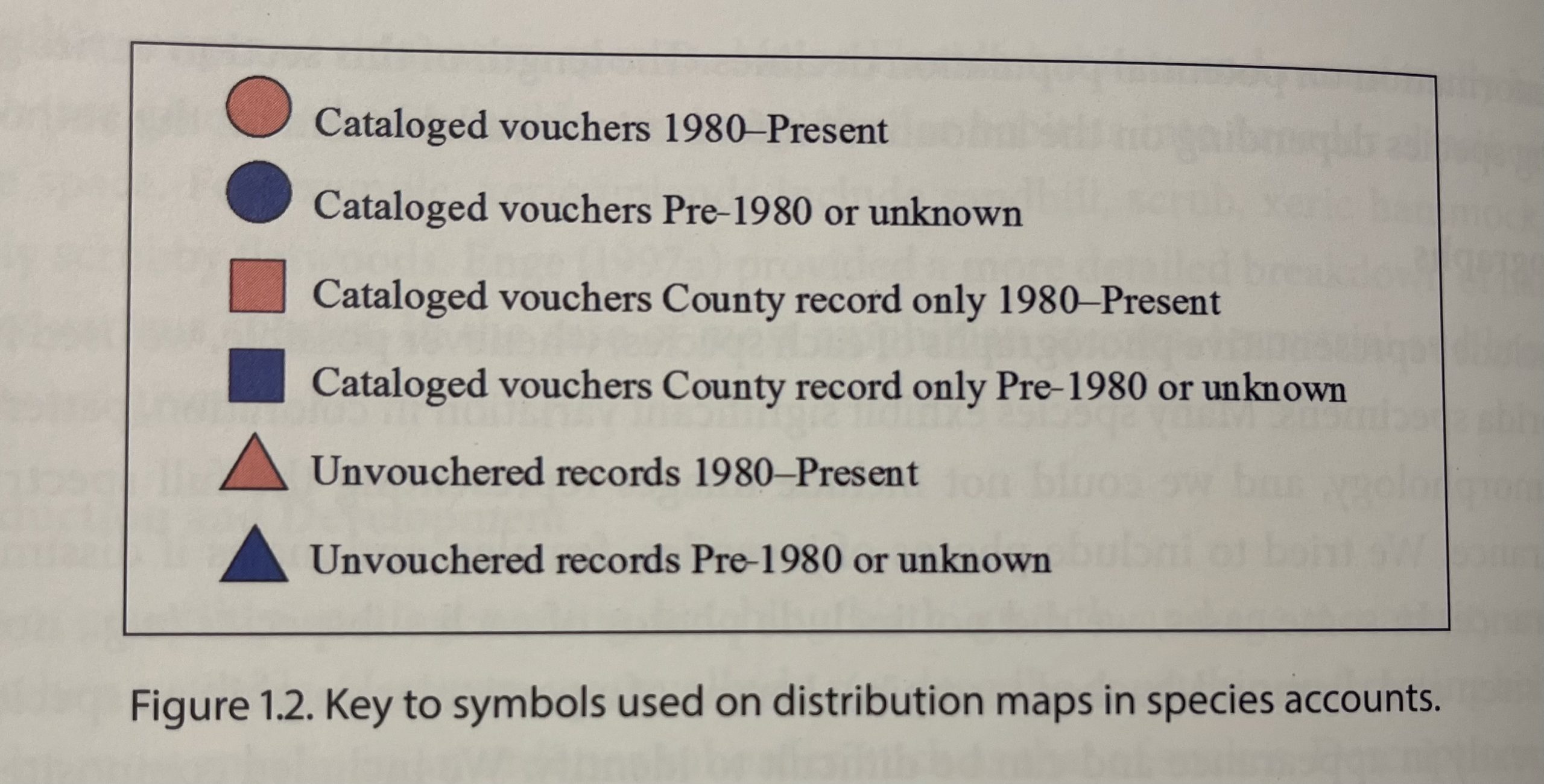

Map keys from the amazing Reptiles and Amphibians of Florida book